Healing Shame Through Connection: Why We Can’t Do It Alone

Image Credit: JSB Co.

Shame has a way of convincing us that the only respectable way to deal with it is on our own.

Maybe you’ve tried to read self-help books, making sure you pick the biggest authors so you curate the best-of-the-best, learn the language of “empathy” and “projection” from social media. Maybe you’ve promised yourself you’ll meditate more, journal more, sort yourself out before ever involving another human being.

And in some ways, that makes total sense. When you’re carrying something that feels unlovable, the idea of showing it to someone else can feel like hell.

But I believe there is a limit to how far we can go with shame in isolation.

This blog is about why healing shame so often needs the antidote of connection which can restore the distorted lens through which you see yourself, the world and others.

There’s no shame in needing another mind and nervous system and another pair of eyes on your experience. We’re just built that way.

How Shame Pushes Us to Hide

Shame doesn’t just murmur “you did something wrong” (remember, that’s guilt!) It goes for the jugular:

“You are wrong.”

“You’re unlovable.”

“If people really knew this about you, you’d be alone.”

When those messages play on repeat, hiding feels like the only safe option:

keeping your struggles private.

over-functioning and proving yourself at work.

using self-help like self-flagellation, trying to “improve” yourself until you’re finally acceptable.

There’s a line in The Departed film, where Mark Wahlberg’s character talks about treating the FEDs like mushrooms: “feed them shit and keep them in the dark.” I think it won’t be inaccurate to say that that’s how shame often treats us.

On the contrary, there’s also a way “too much exposure” can feel like a threat. It can feel like being dragged into a courtroom, the carpet nailed down and ripped up, revealing everything underneath suddenly to a harsh spotlight. For many people, that’s what they imagine will happen if they tell someone their story.

So we’re left with a painful dilemma which is to either stay in the dark with our shame, or risk a court-of-law style exposure.

No wonder so many people stick with the first option for years.

Image Credit: Getty Images

Why We Can’t Fully Untangle Shame Alone

When you’re buried in shame, your inner voice is not a respectful referee. It has already decided the verdict.

Trying to work through shame alone often looks like:

replaying events and always coming to “I’m the problem.”

using meditation or philosophy to float away from yourself, rather than towards yourself.

endlessly analysing your patterns without ever feeling more human so we drift towards doing rather than being.

There are solo paths like certain forms of Buddhist meditation, for example, where it invites you to step back from the sense of “I” altogether. For some people, that’s deeply helpful. However, for others, it can become another sophisticated escape route: a way of bypassing pain rather than meeting it.

The core issue is that shame is deeply and inherently relational. It’s about how you imagine you appear in the eyes of others. You learned shame somewhere, typically in earlier life within families, schools, peer groups, and cultures that made certain parts of you unwelcome.

It makes sense that something learned in relationship often needs relationship to be reworked.

Philosophers have been onto this for a long time. Aristotle, in the Nicomachean Ethics Book VIII, talks about the importance of friendship not just as something nice to have, but as a central ingredient of a good life. Friends are the people in whose presence we come to know ourselves, not just in our heads but in how we’re actually received.

When shame is running the show, we need at least one person who isn’t looking at us through that punitive lens. Someone who isn’t passing judgement. Someone who doesn’t bolt when they see the thing you’re most afraid of.

What Healing Through Connection Looks Like in Therapy

Image Credit: Wesley Tingey

In the consulting room, I regularly tend to witness a particular moment.

A client will eventually share the thing that sits at the root of their distress which is the detail they’re most ashamed of, a memory they swore they would take to the grave alone. Often they’re waiting for me to recoil and judge them, and to thus change how I see them.

And then… nothing catastrophic happens.

I don’t run away. I don’t gossip. I don’t humiliate them. We stay in the room together.

After some initial surge of anxious energy, very often, their shoulders drop and their breathing changes. The tightness in their jaw or chest eases. It’s subtle, but almost miraculous and such a privilege to watch. Something unclenches inside because the worst-case scenario didn’t come true.

Part of what helps is simply naming things out loud.

Think of the Harry Potter books. For years, everyone calls Voldemort “He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named”. Not saying his name becomes a way of feeding the fear. The turning point comes when characters start saying “Voldemort” because it stops colluding with the terror.

Shame works in a similar way. When something stays completely unnamed, it reconvenes in the dark. When you say, “This is what happened” or “This is what I’m afraid I am,” in front of someone who doesn’t flinch, the thing itself doesn’t disappear, but it loses some of its power. A clichéd notion, but it’s true.

In practice, the healing often lives in very small moments:

I remember a detail you told me weeks ago and bring it back at the right time.

I ask how you are after something big you mentioned in passing.

I challenge a particularly vicious bit of self-talk, with some (annoying) curiosity about where it came from rather than tell you to simply ignore it.

I stay put when you expect me to leave.

Researcher Brené Brown uses the metaphor of a “marble jar” to describe this. Trust is built when someone quietly puts marbles in the jar over time through small acts of care, reliability and non-judgement, rather than one grand gesture.

Therapy, at its best, becomes one of the places where those marbles accumulate.

It’s Not Just Therapy: Friends, Partners and “Marble Jar” People

Image Credit: Christine Tan

Therapy is one kind of connection, but it’s not the only place shame can begin to loosen its grip.

Romantic partners can be powerful allies here. Being with someone who doesn’t weaponise your vulnerabilities and who doesn’t use your confessions as ammunition later, continual exposure to that kind of relationship can start to rewrite what love feels like.

Friendships are also hugely underrated in this respect. Again, Aristotle wasn’t wrong in that good friendships are a form of shared life. The people you can text at 2am, and those who know your family dynamics, and those who care about whether you got home safe.

Brené Brown calls these “marble jar friends.” These are the people who, through lots of small moments over time, have shown that your trust is safe with them.

Some other spaces can also matter, especially around identity and culture:

faith communities.

support groups.

online communities where people share marginalised experiences, and other spaces.

Sometimes a friend or therapist might be incredibly well-intentioned but still miss something crucial because they don’t share your background, race or lived experience. It’s not necessarily because they’re uncaring, it’s because there are certain layers of shame and oppression that can be hard to fully grasp from the outside.

It’s absolutely okay to seek out people who fully “get it”, in that sense. That might be another Black person when you’re carrying racialised shame in a predominantly white environment, or someone queer when you’re processing internalised homophobia, or any other shared context that makes you feel less alone.

And, importantly: you don’t have to share everything with everyone. You can talk to different people about different things.

I was reminded of this recently while playing a video game where one character, after working through her own demons and feeling relieved, didn’t push her friend to do the same. She understood, intuitively, that being close doesn’t mean demanding equal levels of exposure. I believe that kind of respect for unspoken boundaries is a form of love.

A Brief Word on AI and “Connection”

It would be strange given that you’re reading this online and we’re all now living with AI, not to name it.

Tools like ChatGPT can sometimes feel like a kind of “connection” where you can have a place to type out thoughts, get reflections, be pointed to ideas or language you didn’t have before.

That can always be useful as a learning tool. I don’t believe there’s anything shameful about seeking information or support from technology.

Image Credit: Getty Images

But there are some caveats:

An AI doesn’t have a body or a nervous system. It can’t sit with your physiology or your trembling hands or your increasing breathing rate.

It doesn’t have skin in the game. It’s not risking anything by knowing your story.

and, it can’t offer the kind of mutual, real-time presence that comes from another human being holding you in mind.

So while AI might help you think about shame in new ways, it cannot replace the experience of being received by an actual human where you have someone who remembers you, worries about you, and is changed by knowing you. Believe it or not, therapists are changed by the clients they work with.

If you find yourself leaning heavily on AI chats as your main outlet, that might be a sign that your system is psychologically and emotionally hungry for real-world connection too.

How Do You Actually Start Letting People In?

Okay so, great Ben, it all sounds nice in theory but what about in practice.

When you want connection after years of hiding, it can be tempting to swing to the other extreme involving total exposure, everywhere, to everyone which has its own kind of risk.

Before we get into some things you can consider, I want to bring in a character from a literary classic.

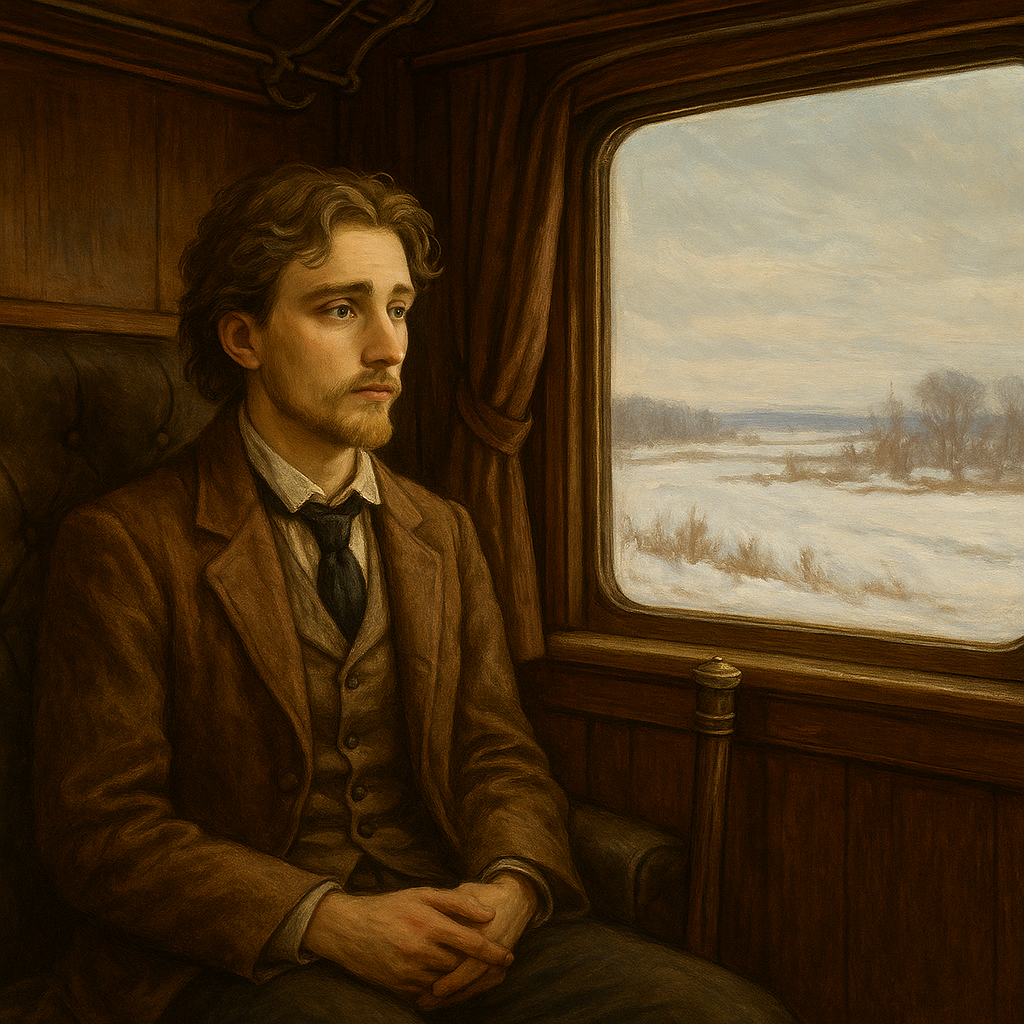

AI-generated image of Prince Myshkin in Dostoevsky’s The Idiot

In Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Idiot, Prince Myshkin is an almost painfully sincere young man. He is open, trusting, and unusually honest about what he sees and feels. His innocence is so disarming that it cuts through social and psychological games and defences in a way that can be deeply moving.

But this stance also leaves him exposed.

People around him don’t all respond with care and admiration. Some are drawn to his openness, some are unsettled by it, and some see it as an opportunity to mock, manipulate or dismiss him as naïve and his lack of armour makes him totally vulnerable.

He’s a good reminder that “healing through connection” isn’t about becoming like Myshkin with everyone you meet by walking around with your chest permanently open to attack. However, we live in workplaces, families, group chats and small towns, rather than monasteries or novels, so therefore the context matters.

So we’re looking for something in between:

not hiding everything in the dark,

not throwing yourself to the wolves,

but practising thoughtful and gradual openness with people who show they can be trusted.

With that in mind, here are a few small, realistic starting points.

1. Notice who already adds “marbles” to your jar

Trust is a good one to start with.

Think about the people in your life now. Who:

remembers small details about you?

checks in after a hard thing, even briefly?

has shown they can keep something in confidence?

You don’t have to dump your whole life story on them. But you might experiment with sharing 5% more truth with one of those people than you usually would.

2. Practise staying present in your body when you share

Shame loves to drag you out of your body into overthinking, imagining worst-case scenarios and initiating self-attack.

If it feels safe enough, you could try:

Feeling your feet on the floor as you speak.

Lengthening your out-breath slightly if you feel panicky.

Or even rubbing your hands together if you feel numb.

Perhaps also noticing: “Ah, here’s that familiar hollow feeling in my stomach as I say this”, without forcing it to disappear.

In polyvagal terms, these kinds of cues can help your system move towards a calmer and more socially-engaged state (ventral vagal), the state where connection is possible, rather than everything being framed as threat.

3. Choose your audience with care

Healing through connection is not the same as:

Confessing everything to everyone (like Prince Myshkin).

Trauma-dumping on whoever is nearby.

Or forcing yourself to reconcile with people who have consistently harmed you.

You’re allowed to be discerning. You’re allowed to say “no” to unsafe people. You’re allowed to take your time.

As one of my psychotherapy trainers put it: working slowly is working quickly. Rushing yourself into massive disclosures can backfire. Letting trust accumulate in small steps tends to be more sustainable.

An Important Aside

You might have read the list in 1) and think, “I don’t have anyone like that.”

If that’s you, that absence can feel like its own kind of shame:

“Everyone else seems to have a friend or partner they can lean on. What does it say about me that I don’t?”

It’s worth saying this very clearly: not having “marble jar people” right now is not proof that you’re unworthy of them. It usually says more about what you’ve lived through, for example, the family you grew up in, the places you’ve worked, the culture you live in, than it does about your lovability.

Image Credit: Alex Shuper

If your mind draws a blank when you scan your life for safe people, it may just mean that:

You’ve spent years in environments where vulnerability was punished or mocked.

Or, you’ve learnt to be the helper, listener or carer, and no one has reciprocated.

Or, you’ve had to move, start again, or live in a way that made lasting bonds hard to build.

For some people, therapy can be the first “marble jar” relationship which is the first place where their inner world is held in mind, remembered, and not used against them. That’s a big part of why the work can feel so different to everyday conversations.

If that’s the stage you find yourself in, your “connection work” might look less like choosing between several trusted people and more like:

Allowing yourself to test out being a bit more real in therapy.

Noticing what it’s like to have someone remember you, session to session.

And, slowly letting the possibility in that people could, in time, show up for you in other contexts as well.

From there, later on, you might experiment with:

Low-stakes group spaces (classes, interest groups, online communities that feel aligned with who you are)

Very small acts of contact, like a brief message, a reply, or a coffee, rather than instant best-friend-level sharing

It’s completely okay if you’re not there yet. If the only honest answer right now is, “I don’t have anyone in my life who feels safe enough,” that deserves to be acknowledged and not glossed over. Sometimes the first step isn’t finding the perfect person, but admitting how lonely it has actually been. From there, different choices can slowly become possible.

You’re Not the Only One Dealing With This

Shame loves to tell you that you are uniquely awful and that everyone else seems to be getting on with life while you’re quietly falling apart.

In reality, shame is everywhere. It’s baked and burnt into how many of us were raised, how schools operated, how workplaces rewarded or punished us, and how our cultures talk about bodies, success, race, gender and sexuality.

Most people you pass on the street are walking around with unsaid stories and hidden pains. In a strange way, hiding parts of ourselves has become indicative of how we function in the modern world, like a kind of social agreement that keeps us all from being overwhelmed by each other’s rawness.

The goal isn’t to suddenly disclose everything to everyone. That would turn our brains to scrambled eggs.

The aim is more modest as well as being more radical, which is to find a few people, in a few places, where you no longer have to pretend so hard.

A Personal Note (and an Invitation)

I don’t write about shame from a safe and detached distance. I’ve had my own experiences with it, and I don’t think it’s something that ever completely vanishes.

What has changed for me over time is the relationship I have with it, and connection has been central to that. The people who didn’t run. The mentors and friends who saw more of me than I was comfortable showing, and stayed anyway. The therapist who got into the trenches with me. The clients who have trusted me with their stories and, in doing so, quietly reminded me of our shared humanity.

If any of this resonates and you’d like a space where your shame, self-criticism or your sense of not being enough can be met with curiosity rather than judgement, you’re more than welcome to reach out.

I offer online hypno-psychotherapeutic counselling, working one-to-one with people who are tired of carrying this alone.

No more feeling alone.

Image Credit: Nico Smit